by

Aubrie CoxWhen I found there was such a form as linking stories, I felt right at home. Working with forms such as haiku, tanka, and renku, I am expected to link from one image to the next, from one poem to the next. For example:

empty house

ghost stories seeping

into the walls

shadows shift

on yesterday’s paper

(from "Ghost Stories" by Aubrie Cox, Notes From the Gean 3.3, December 2011)These two links of the renku are separate images that are easy to imagine separately, but when put together, they create a new thing--a new experience and a bigger picture that would not have existed otherwise. While the second link expands the feelings of emptiness, loneliness, it also shifts to a slightly different, but related, thought (old stories). This is basically how I view linked stories.

For my project this semester, I came in with material that I had been trying to shape to meet these expectations, while also blending haiku aesthetics (nature-oriented, objectivity, capturing a moment and little things, and room for interpretation) with the conventions of fiction (story, plot, character). These stories had a reoccurring character with a reoccurring structure (lines of a single haiku integrated throughout the story, and then the full poem at the end of the story). The mistake was that I was using a very

traditional, manuscript format for a very experimental writing.

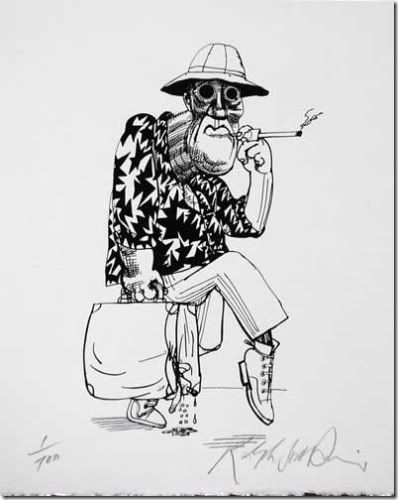

It was kind of like trying to paint a Ralph Steadman piece using Michelangelo's brush.

First Day of Creation by Michelangelo from Web Gallery of Art

First Day of Creation by Michelangelo from Web Gallery of Art DR Gonzo Mono by Ralph Steadman from signatureillustration.org

DR Gonzo Mono by Ralph Steadman from signatureillustration.orgBy the time I got to workshop, there was a lot of discussion among the group about how the extension description worked, and how it didn't (mostly didn't). I remember our professor reading through one section and suddenly saying, "Wait! Something's happening here, but I almost missed it among all this description." That was the first little "ah ha" moment—okay, so I need to make sure I'm not burying the action. And she went on to say that I should consider reparagraphing and examining the space on the page. The little "ah ha" suddenly became "AH HA!"

As writers, we often discuss how to write so that the reader keeps turning the pages; what I needed to do was figure out how to keep the reader reading from sentence to sentence. I had to link moment to moment.

I started with this:

And ended with this:

Of course, I'm sure the burning question is...

how? Well, for starters, as recommended by Cathy, I read Sean Lovelace's

Fog Gorgeous Stag to see how words could be rearranged on the page, and how white space played just as much a part in the composition as the words. To realize that, yes, I am allowed to start moving around the text to create a different visual experience (and therefore reading experience) was absolutely liberating.

Step 1: Rip Apart the ParagraphsBefore I could gut my work, I had to take a good hard look at it. I had to read each individual sentence to examine how it functioned with the whole, and then determine how much space it deserved on the page. The questions I asked myself usually included:

What does this sentence do?

How important is the information in the sentence?

Does it deserve to be alone or does it work better with several sentences?

Most paragraphs were broken down into three sections at the very least.

Step 2: Exodus from the Word ProcessorMicrosoft Word and I don't necessarily get along. No matter how many auto functions I turn off, I still find myself fighting with the program to make it do what I want to do. So one of the first things I asked was, "Can I do it in InDesign?"

Adobe InDesign, which is a program designed to create page layouts for print and digital publications, gave me more flexibility to move and shape type in pieces at a time in ways that would have probably given Word an aneurism.

Eat your heart out, Word.

Eat your heart out, Word.If I wanted to move a couple sentences of from one side of the page to the other, or make one section a block while the sentence after stretched across the page, I could do so without worrying about the rest of the page changing on me.

Step 3: Like Information Does Like ThingsIt took a while before I figured out what I wanted my system to be—I knew I couldn't just randomly throw words into the file and arrange them to where I thought, "That looks pretty!"

The first thing that clicked for me was dialogue. To further distinguish who was talking, I put one character's dialogue to the left side of the page, and the other to the right (I always had only two characters talking at a time). It was quite revealing to see which characters dominated conversations, and in some cases, I think will also be revealing to the reader.

Throughout the stories, the patterns vary, but on each individual page (or spread), sections of text have been laid out to reflect similarities in the content or how much attention that passage deserves.

Step 4: Movement Across the Page (Linking of Ideas)When I write scenes, I usually have a sense of movement in my mind. The eternal camera sweeps across the scenery in a particular direction, and I was able to mimic that movement in the layout of the pages. In a photograph, you want to direct the viewer's eye from one side of the picture to the other, to direct him or her to a focal point. On the page, I wanted to direct the reader from one passage to the next.

This is where the linking becomes most apparent, both in layout and the text. If the next passage is closely related (such as, a cause and effect moment), it is probably a closer proximity than a passage that shifts the direction of the story (action to dialogue). In considering what the consequence the next moment or even next sentence has on the previous text determined where I placed it on the page. Meanwhile, I tried to keep in mind that the reader's eye would have to be directed to the next sentence/passage.

Overall, I feel as though I came out of this project with a new way to compose my fiction. By breaking it down into small portions, I could focus on the individual words and create manageable portions for my reader to keep him or her from getting bogged down in the details while also pausing to appreciate the little things.